Why it matters: Traditional artificial limbs are getting better, but they just don't quite achieve that smooth, natural stride most people take for granted. They rely on robotic sensors and programs to 'fake' a normal gait, so it's far from perfect. Now, researchers from MIT and Brigham and Women's Hospital have an innovative solution that puts the control right back where it belongs – in the user's brain.

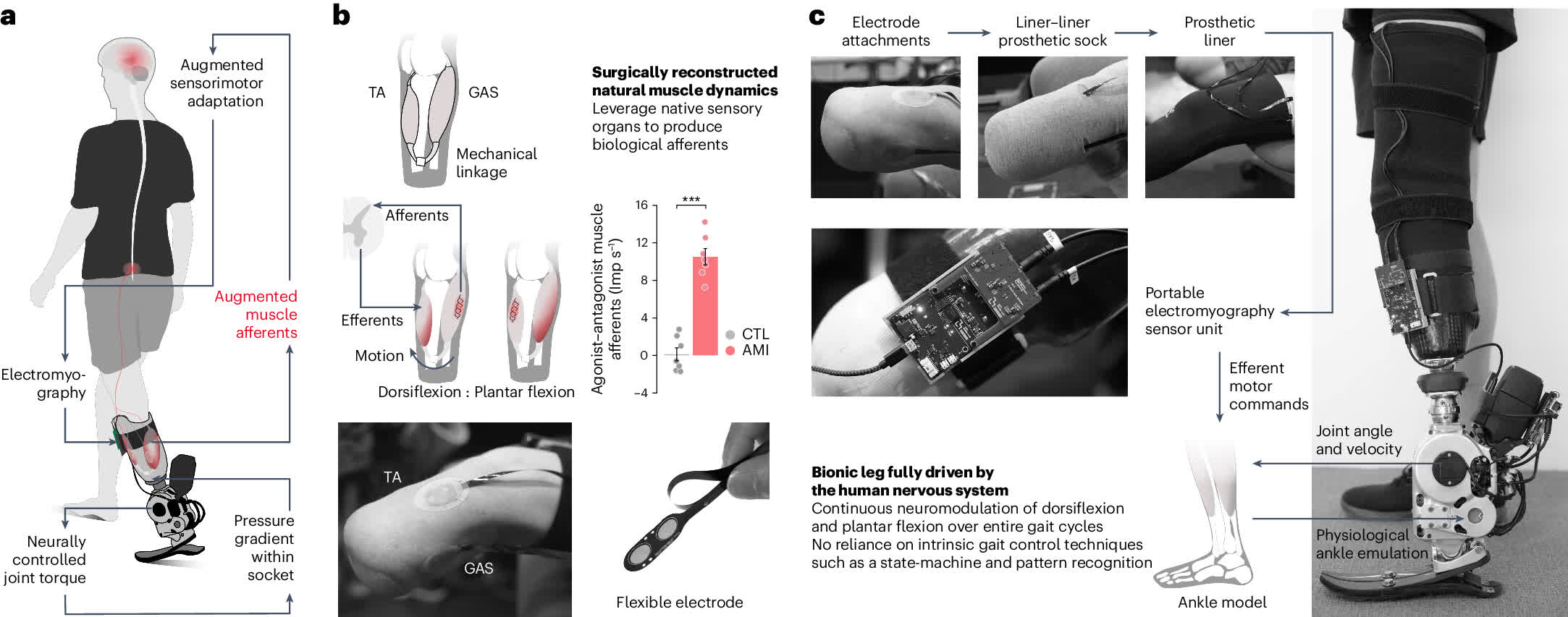

The study, published last month in Nature Medicine, details a pioneering surgical technique called the agonist-antagonist myoneural interface (AMI). It's a new approach to amputation that aims to preserve the neural and muscular connections needed for seamless limb control.

Essentially, AMI reconnects prosthetic limbs to muscles in the residual limb so the pair can still "talk" to each other and relay that vital position sense up to the brain. These muscle signals get processed by a robotic controller that determines how far to bend the prosthetic ankle joint, along with calculating the necessary torque and power output.

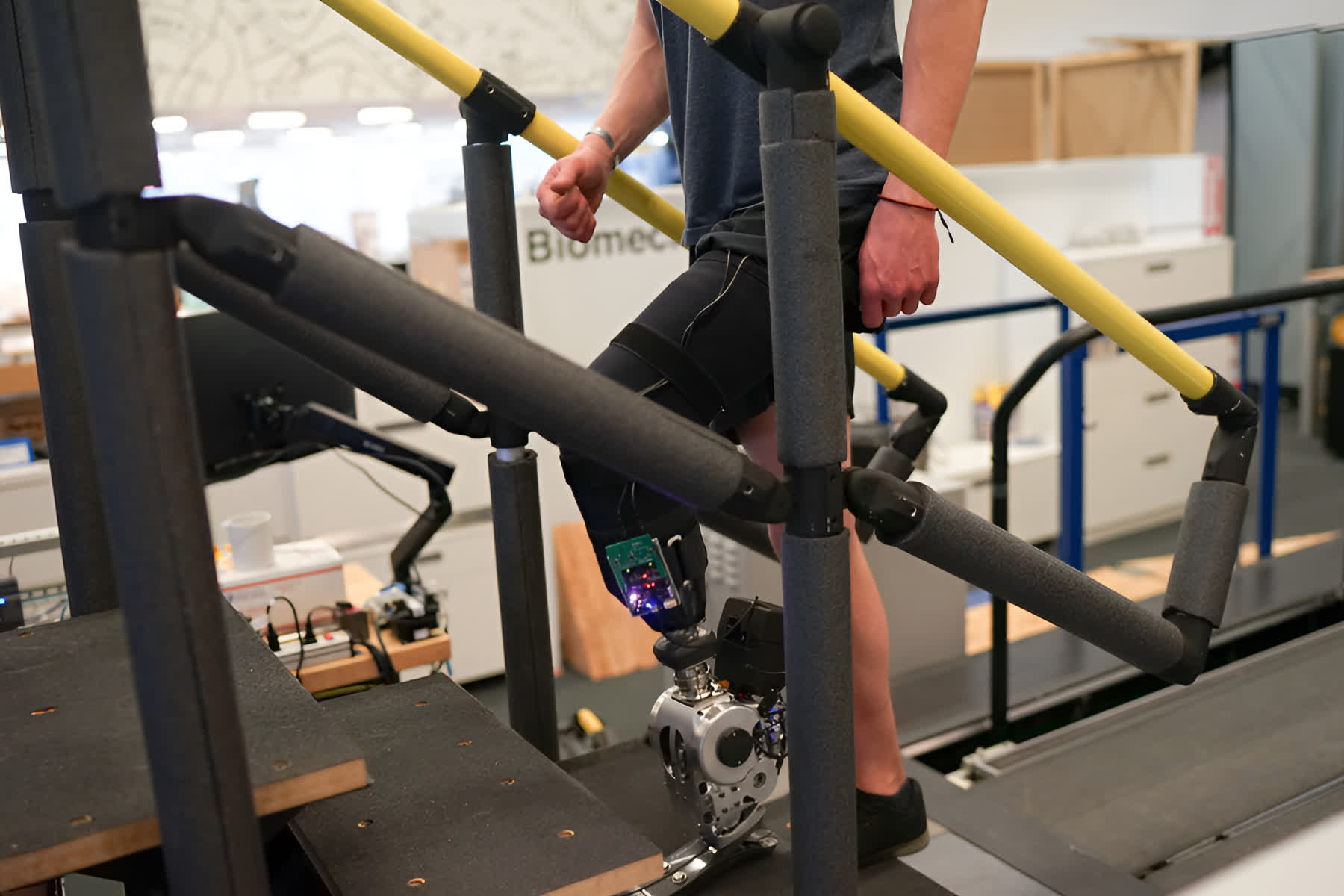

The team tested this interface on seven AMI patients fitted with powered prosthetic legs. The results were pretty mind-blowing – the AMI folks were strolling at normal speeds, automatically adjusting for slopes and obstacles, and even nailing more complex moves like pointing the toes of the prosthesis upward while climbing stairs.

Lead researcher Hugh Herr calls it the "first prosthetic study in history" to show full neural modulation of a leg. Here, the nervous system alone drives a natural biological gait, independent of any robotic control algorithm. Essentially, the AMI tricks the brain into thinking the prosthetic is just another biological limb under its direct command.

How did such limited neural input unlock this full spectrum of movement? According to grad student Lenny Song, "A small increase in neural feedback from your amputated limb can restore significant bionic neural controllability, to a point where you allow people to directly neurally control the speed of walking, adapt to different terrain, and avoid obstacles."

The researchers compared the AMI group to seven people with traditional amputations using the same powered prosthetic legs. The AMI patients outperformed them on every metric – faster walking speeds, smoother movements, and better coordination between prosthetic and intact limbs. They could even push off the ground with normal force.

The AMI patients also saw less pain, muscle atrophy, and other nagging issues from traditional amputations. Although their limbs were getting only around 20% of the normal neural data, it was enough for the brain's hidden talents for biomimetic motion to take over.

Of course, the current AMI procedure is still complex surgery. But Herr's ultimate vision involves "rebuilding human bodies" by merging biological systems with mind-controlled bionics.